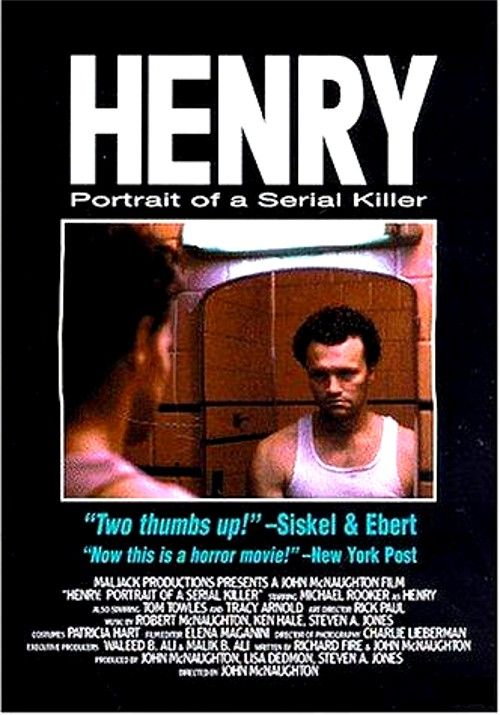

| Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer | |

|---|---|

| Directed by | John McNaughton |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by | |

| Starring | |

| Music by | |

| Cinematography | Charlie Lieberman |

| Edited by | Elena Maganini |

| Distributed by | Greycat Films |

Release date |

|

| 83 minutes | |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $110,000[1] |

| Box office | $609,939 (US)[2] |

- Henry The Serial Killer Movie

- Harry The Serial Killer

- Henry Serial Killer Hotel

- Portrait Of A Serial Killer

Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer is a 1986 American psychological horrorcrime film directed and co-written by John McNaughton about the random crime spree of a serial killer who seemingly operates with impunity. It stars Michael Rooker as the nomadic killer Henry, Tom Towles as Otis, a prison buddy with whom Henry is living, and Tracy Arnold as Becky, Otis's sister. The characters of Henry and Otis are loosely based on real life serial killers Henry Lee Lucas and Ottis Toole.

Henry was filmed in 1985 but had difficulty finding a film distributor. It premiered at the Chicago International Film Festival in 1986 and played at film festivals throughout the late 1980s. Following successful showings during which it attracted both controversy and positive critical attention, it was rated 'X' by the MPAA, further increasing its reputation for controversy. It was subsequently picked up for a limited release in 1990 in an unrated version. It was shot on 16mm in less than a month with a budget of $110,000.

- 4Release

- Henry Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986) is a dark and terrifying film. The opening 10 to 15 minutes are extremely effective, as we follow Henry (Michael Rooker) while he is on the prowl looking for his next victims. Intercut between this is images of the grizzly aftermath of his killings.

- Serial killer Henry Louis Wallace killing spree began in 1990 with the murder of Tashonda Bethea in his hometown of Barnwell, South Carolina. He went on to rape and murder nine women in Charlotte, North Carolina between 1992 and 1994.

Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, 1986. Directed by John McNaughton. Starring Michael Rooker, Tom Towles and Tracy Arnold. Filmed in a documentary style, Henry: Portrait of Serial Killer (1986. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer is a 1986 American psychological horror crime film directed and co-written by John McNaughton about the random crime spree of a serial killer who seemingly operates with impunity. The new Investigation Discovery documentary Bad Henry introduces viewers to serial killer Henry Louis Wallace, who murdered Black women in Charlotte.

Plot[edit]

Henry is a drifter who murders scores of people - men, women, and children - as he travels through America. He migrates to Chicago, where he stops at a diner, eats dinner, and kills two waitresses.

Otis, a drug dealer and prison friend of Henry's, picks up his sister Becky, who left her abusive husband, at the airport. Otis brings Becky back to the apartment he shares with Henry. Later that night, as Henry and Becky play cards, Becky asks Henry about the murder of his mother, the crime that landed him in prison. He tells her he stabbed his mother because she abused and humiliated him as a child, though he later claims he shot her. Becky reveals that her father raped her as a teenager.

The next day, Becky gets a job in a hair salon. That evening, Henry kills two prostitutes in front of Otis. Otis, though shocked, feels no remorse. He does, however, worry that the police might catch them. Henry assures him that everything will work out. Back at their apartment, Henry explains his philosophy: the world is 'them or us'.

Henry and Otis go on a killing spree together. Henry says that every murder should have a different modus operandi so the police will not connect various murders to one perpetrator. He also explains that it is important never to stay in the same place for too long; by the time police know they are looking for a serial killer, he can be long gone. Henry tells Otis that he will have to leave Chicago soon. The pair then slaughter a family, while recording the whole incident on their video camera, then watch it back at their apartment.

Becky quits her job so she can return home to her daughter. Otis and Henry argue after their camera gets destroyed while Otis is filming female pedestrians from the window of Henry's car. Otis gets out of the car and goes for a drink, while Henry returns to the apartment. Becky tells Henry her plans, and they decide to go out for a steak dinner. After, she tries to seduce him, but he seems scared of her advances. A drunken Otis enters and asks if he's interrupting anything. Embarrassed, Henry leaves to buy cigarettes. He returns to find Otis has raped Becky and is strangling her. Henry kicks Otis off her and a fight ensues. Otis gets the upper hand and smashes a bourbon bottle onto Henry's face. Otis is about to kill Henry when Becky stabs Otis in the eye with the handle of a metal comb. Henry stabs Otis, causing him to bleed to death, and dismembers his body in the bathtub, telling Becky that calling the police would be a mistake.

Henry and Becky dump Otis's body parts in a river and leave town. Henry suggests that they go to his sister's ranch in San Bernardino, California, promising Becky they will send for her daughter when they arrive. In the car, Becky confesses that she loves Henry. 'I guess I love you too', Henry replies, unemotionally. They book a motel room for the night.

The next morning, Henry leaves the motel alone, gets into the car and drives away. He stops at the side of the road to dump Becky's blood-stained suitcase in a ditch, then drives away.

Cast[edit]

- Michael Rooker as Henry

- Tom Towles as Otis

- Tracy Arnold as Becky

Production[edit]

In 1984, executive producers Malik B. Ali and Waleed B. Ali of Maljack Productions (MPI) hired a former delivery man for their video equipment rental business, John McNaughton, to direct a documentary about gangsters in Chicago during the 1930s. Dealers in Death was a moderate success, and was well received critically, so the Ali brothers kept McNaughton on as director for a second documentary about the Chicago wrestling scene in the 1950s. A collection of vintage wrestling tapes had been discovered, and the owner was willing to sell them to the Ali brothers for use in the documentary. However, after financing was in place, the owner doubled his price and the brothers pulled out of the deal. With the documentary cancelled, Waleed and McNaughton decided that the money for the documentary could instead be used to make a feature film. The Ali brothers gave McNaughton $110,000 to make a horror film with plenty of blood.[citation needed]

McNaughton knew the budget would be too small to make a horror film about aliens or monsters, and was unsure what to do until he saw an episode of 20/20 about the serial killer Henry Lee Lucas. McNaughton decided to film a fictional version of Lucas's crimes.[citation needed]

In the meantime, the Ali brothers brought Steven A. Jones onto the project as a producer, and Jones hired Richard Fire to work as McNaughton's co-writer. With the producer, writer, and director in place and with the subject matter decided upon, the film went into production.[3][4][5]

Henry was shot on 16mm in only 28 days for $110,000 in the year of 1985. During filmmaking, costs were cut by employing family and friends wherever possible, and participants utilized their own possessions. For example, the dead couple in the bar at the start of the film are the parents of director John McNaughton’s best friend, while the bar itself is where McNaughton once worked. Actress Mary Demas, a close friend of McNaughton’s, plays three different murder victims: the woman in the ditch in the opening shot, the woman with the bottle in her mouth in the toilet, and the first of the two murdered prostitutes. The four women Henry encounters outside the shopping mall were all played by close friends of McNaughton. The woman hitchhiking was a woman with whom McNaughton used to work. The clothes Michael Rooker wears throughout the film were his own (apart from the shoes and socks). The 1970 Chevrolet Impala driven by Henry belonged to one of the electricians on the film. Art director Rick Paul plays the man shot in the layby; storyboard artist Frank Coronado plays the smaller of the attacking bums; grip Brian Graham plays the husband in the family-massacre scene; and executive producer Waleed B. Ali plays the clerk serving Henry towards the end of the film.[3]

Rooker remained in character for the duration of the shoot, even off set, not socializing with any of the cast or crew during the month-long shoot. According to the costume designer Patricia Hart, she and Rooker would travel to the set together each day, and she never knew from one minute to the next if she was talking to Michael or to Henry as sometimes he would speak about his childhood and background not as Michael Rooker but as Henry. Indeed, so in-character did Rooker remain, that during the shoot, his wife discovered she was pregnant, but she waited until filming had stopped before she told him.[5]

Because the production had so little money, they could not afford extras, so all of the people in the exterior shots of the streets of Chicago are simply pedestrians going about their business. For example, in the scene where Becky emerges from the subway, two men can be seen standing at the top of the stairs having a heated discussion. These men were really having an argument, and when the film crew arrived to shoot, they refused to move, so John McNaughton decided to include them in the shot.[citation needed]

After filming was finished, there was so little money left that the film had to be edited on a rented 16 mm flatbed which was set up in editor Elena Maganini's living room.[citation needed]

Release[edit]

MPI did not plan a theatrical release for the film. McNaughton himself sent copies of the film to prominent film critics, hoping to attract attention and thus a distributor. Vestron was the first distributor to show an interest in the film, but they pulled out over home video distribution disputes with MPI and fears of a potential lawsuit due to the film's use of real names. Following this, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer premiered at the Chicago International Film Festival on September 24, 1986. In 1988, MPI hired Chuck Parello, who worked to get the film in theaters. The film played at several festivals throughout 1988 and 1989, where it attracted increasing amounts of attention. This culminated in positive attention from Roger Ebert at the Telluride Film Festival in 1989. Atlantic Entertainment Group expressed interest in releasing the film theatrically but mandated that it have an MPAA 'R' rating. The MPAA responded with an 'X' rating, which was popularly associated with pornographic films at the time.[6] In Roger Ebert's review of the film, he writes that the MPAA told the filmmakers that no possible combination of edits would have qualified their film for an R rating, indicating that the ratings issue did not simply involve graphic violence. He also went on to say that the film was an obvious candidate for the then-proposed A rating for films that were for adults-only which were non-pornographic.[7] This film, along with Peter Greenaway'sThe Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover and Pedro Almodóvar's Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, were the instigation for the creation of an adults-only rating for non-pornographic films, NC-17. Due to the rating, Atlantic pulled out. Following further controversy over the rating, Greycat Films picked up the film for distribution after it screened at the Boston Film Festival in 1989. Its theatrical premiere, a limited release, was on January 5, 1990, during which it grossed $609,000, in part due to the continued controversies surrounding the film. McNaughton credited the MPAA's refusal to accept any cuts as giving him the opportunity to release it uncut, as he would have made cuts had they requested it.[8]

Further censorship[edit]

In the UK, the film has had a long and complex relationship with the BBFC.[9] In 1991, distributor Electric Pictures submitted the film for classification with 38 seconds already removed (the pan across the hotel room and into the bathroom, revealing the semi-naked woman on the toilet with a broken bottle stuck in her mouth). Electric Pictures had performed this edit themselves without the approval of director John McNaughton[citation needed] because they feared it was such an extreme image so early in the film, it would turn the board against them. The film was classified '18' for theatrical release in April 1991, after 24 seconds were cut from the family massacre scene (primarily involving the shots where Otis gropes the mother’s breasts both prior to killing her and after she is dead).[citation needed]

In 1992, Electric Pictures submitted the pre-cut theatrical print of the film to the BBFC for home video classification, once again missing the shot of the dead girl. In January 1993, the BBFC again classified the film '18', but the Board also removed four seconds from the scene where the TV salesman is murdered, meaning a total of 42 seconds were removed from the home video release. However, BBFC director James Ferman overruled his own team and demanded that the family massacre scene be trimmed down to almost nothing, removing 71 seconds of footage. Additionally, Ferman re-edited the scene so that the reaction shot of Henry and Otis watching TV now occurred midway through the scene rather than at the end. Total time cut from the film: 113 seconds.[10]

In 2001, Universal Home Entertainment submitted the full uncut version of the film for classification for home video release. The BBFC waived the four seconds cut from the murder of the TV salesman, and 61 of the 71 seconds from the family massacre scene (they refused to reinstate the 10 seconds of the scene where Otis molests the mother after she is dead). Additionally, they partly approved the 38 second shot of the dead woman on the toilet, but they demanded that the last 17 seconds of the shot be removed. Based upon this, Universal decided to remove the shot entirely.[citation needed]

In 2003, Optimum Releasing again submitted the full uncut version of the film for classification for a cinema release, and later for a home video release. In February 2003, the BBFC passed the film completely uncut, and in March 2003 the uncut version of the film was officially released in the UK for the first time.[11]

A parallel censoring of the film happened in New Zealand, where the film was originally banned outright by the Film Censor in 1992. A censored version was subsequently released on home video with cuts to the 'family massacre' sequence. The film was finally released uncut on DVD in Australia in 2005; in 2010 another DVD release was approved, apparently without cuts in New Zealand for the first time.[12]

Reception[edit]

Critical reception at its premiere was mixed, and the resulting debate over the film's themes and morality helped to raise its profile.[13] The film's subsequent theatrical release was able to capitalize on positive reviews it had received throughout its controversial festival showings, and it was more positive.[14]Rotten Tomatoes, a review aggregator, reports that 87% of 61 surveyed critics gave the film a positive review; the average rating is 7.58/10. The consensus reads: 'Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer is an effective, chilling profile of a killer that is sure to shock and disturb.'[15] On Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating to reviews, the film has a weighted average score of 80 out of 100, based on 22 critics, indicating 'Generally favorable reviews'.[16]

Critics who liked the film tended to focus on the sense of newness it brought to the saturated horror genre. Roger Ebert, for example, called Henry 'a very good film,' a 'low-budget tour de force,' and wrote that the film attempts to deal 'honestly with its subject matter, instead of trying to sugar-coat violence as most 'slasher' films do.'[7]Elliott Stein of The Village Voice called it 'the best film of the year...recalls the best work of Cassavetes.' Siskel & Ebert called it 'a powerful and important film, brilliantly acted and directed.' Dave Kehr of the Chicago Tribune said it was 'one of the ten best films of the year...combines Fritz Lang's sense of predetermination with the freshness of John Cassavetes.'[17] In a review from 1989, Variety wrote the film 'marks the arrival of a major film talent' in McNaughton.[18]

It is listed in the film reference book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, which says 'Henry evokes horror through gritty realism and excellent acting. The film is not fun to watch, but it is important in that it forces viewers into questioning our cultural fascination with serial killers.'[19]

The film was recognized by American Film Institute in 2003 for their AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains list.[20]

Comparison to real-life source material[edit]

In prison, Henry Lee Lucas confessed to over 600 murders, claiming he committed roughly one murder a week between his release from prison in 1975 to his arrest in 1983. While the film was inspired by Lucas' confessions, the vast majority of his claims turned out to be false.[21][22] A detailed investigation by the Texas Attorney General's office was able to rule out Lucas as a suspect in most of his confessions by comparing his known whereabouts to the dates of the murders to which he confessed. Lucas was convicted of 11 murders, but law enforcement officers and other investigators have overwhelmingly rejected his claims of having killed hundreds of victims. The Texas Attorney General's Office produced the 'Lucas Report', which concluded that reliable physical evidence linked Lucas to three murders.[23][24] Others familiar with the case have suggested that Lucas committed a low of two murders to — at the most — about 40 killings. The hundreds of confessions stemmed from the fact that Lucas was confessing to almost every unsolved murder brought before him, often with the collusion of police officers who wanted to clear their files of unsolved and 'cold cases.' Lucas reported that the false confessions ensured better conditions for him, as law enforcement officers would offer him incentives to confess to crimes he did not commit. Such confessions also increased his fame with the public.[25] Lucas was ultimately convicted of 11 murders and sentenced to death for the murder of an unidentified female victim known only as 'Orange Socks'. His death sentence was commuted to life in prison by the then Governor of TexasGeorge W. Bush in 1998. Lucas died in prison of heart failure on March 13, 2001.[citation needed]

The character of Henry shares many biographical concurrences with Lucas himself. However, as the opening statement makes clear, the film is based more on Lucas' violent fantasies and confessions rather than the crimes for which he was convicted. Similarities between real life and the film include:

- Henry Lee Lucas became acquainted with a drifter and male prostitute named Ottis Toole, whom he had met in a soup kitchen in Jacksonville, Florida. In the film, the character's name is 'Otis' and meets Henry in prison.

- Henry Lee Lucas sexually abused Toole's 12-year-old niece, Frieda Powell, who lived with Lucas and her uncle for many years. As in the film, Frieda Powell preferred to be addressed as 'Becky' rather than her given name. However, in the film Becky is Otis' younger sister and is considerably older than the 12-year-old Frieda Powell.

- As in the film, Lucas' mother was a violent prostitute who often forced him to watch her while she had sex with clients. The mother sometimes would make him wear girl's clothing and dresses. Lucas' father lost both his legs after being struck by a freight train; the character relates a similar story.[citation needed]

Home media[edit]

In the UK, the film was first released in its uncut form in 2003 by Optimum Releasing. The DVD contained a commentary from director John McNaughton (recorded in 1999), a censorship timeline, comparisons of the scenes edited by the BBFC with their original uncut status, two interviews with McNaughton (one from 1999, one from 2003), a stills gallery and a biography of Henry Lee Lucas (text).

In the US, in 2005 a special 20th Anniversary Edition two-disc DVD was released by Dark Sky Films. This DVD included a newly recorded commentary from McNaughton, a 50-minute making-of documentary, a 23-minute documentary about Henry Lee Lucas, 21 minutes of deleted scenes with commentary from McNaughton, a stills gallery, and the original storyboards. This DVD also featured a reversible cover featuring the banned original poster art by Joe Coleman.[26] The film had a Blu-ray release in 2009.

Sequel[edit]

A sequel, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, Part II, was released in 1996. The film was directed by Chuck Parello and starred Neil Giuntoli as Henry with Kate Walsh and Penelope Milford in supporting roles.[27]

Henry The Serial Killer Movie

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Mark Hughes (October 30, 2013). 'The Top Ten Best Low-Budget Horror Movies Of All Time'. Forbes. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ^'Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer'. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ abHenry: Portrait of a Serial Killer: Director's Commentary R2 UK Full Uncut Edition DVD. 2003.

- ^Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer: R1 20th Anniversary Edition DVD, 2005. Director's commentary track

- ^ abPortrait: The Making of Henry. 2005 (Documentary).

- ^Kimber 2011, p. 17–21.

- ^ abEbert, Roger (September 14, 1990). 'Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer'. RogerEbert.com. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^Kimber 2011, p. 19–24.

- ^'Henry - Portrait Of A Serial Killer'. BBFC. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^'Henry - Portrait Of A Serial Killer'

- ^''Censorship Timeline' (R2 UK Full Uncut Edition DVD Featurette)'.

- ^New Zealand Censorship Database

- ^Kimber 2011, p. 18.

- ^Kimber 2011, p. 25.

- ^'Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986)'. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^'Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer Reviews - Metacritic'. Metacritic.com. Metacritic. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^'Stills Gallery (R1 US 20th Anniversary Edition DVD Extra)'.

- ^'Review: 'Henry – Portrait of a Serial Killer''. Variety. October 4, 1989. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^Scheider 2013.

- ^'AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees'(PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ^Brad Shellady, 'Henry: Fabrication of a Serial Killer'. Everything You Know Is Wrong: The Disinformation Guide to Secrets and Lies, 2002. Russ Kick, editor.

- ^'Myth of a Serial Killer: The Henry Lee Lucas Story DVD'. History.com. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^Mattox, Jim (April 1986). 'Lucas Report'. Office of Texas Attorney General. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^Knox, Sara L. (2001). 'The Productive Power of Confessions of Cruelty'. University of Western Sydney/University of Virginia. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^Shellady, 2002

- ^'Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer banned...art by Coleman'. eMoviePoster.com. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^Anita Gates. 'Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, Part 2'. The New York Times.

Sources[edit]

- Kimber, Shaun (2011). Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN9780230343696.

- Scheider, Steven Jay (2013). 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die. Murdoch Books Pty Limited. p. 782. ISBN978-0-7641-6613-6.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer |

- Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer on IMDb

- Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer at AllMovie

- Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer at Box Office Mojo

- Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer at Rotten Tomatoes

- Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer at HouseofHorrors.com

- Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer at RogerEbert.com

Police mug shot of Lucas in 1983 | |

| Born | August 23, 1936 |

|---|---|

| Died | March 12, 2001 (aged 64) Huntsville, Texas, United States |

| Cause of death | Heart failure |

| Other names | The Confession Killer The Highway Stalker |

| Criminal penalty | Death, commuted to life imprisonment |

| Details | |

| Victims | 11 convictions, hundreds more claimed |

| 1960–1983 | |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | Michigan Texas possibly Florida |

Date apprehended | June 11, 1983 |

Henry Lee Lucas (August 23, 1936 – March 12, 2001) was an American serial killer. Lucas was arrested in Texas and on the basis of his confessions to Texas Rangers, hundreds of unsolved murders were attributed to him and officially classified as cleared up. Lucas was convicted of murdering 11 people and condemned to death for a single case with an unidentified victim. A newspaper exposed the improbable logistics of the confessions made by Lucas, when they were taken as a whole, and a study by the Attorney General of Texas concluded he had falsely confessed. Lucas's death sentence was commuted to life in prison in 1998. In some cases, law enforcement thought that Lucas had demonstrated knowledge of facts that only a perpetrator could have known.

- 1Early life

- 2Drifter

- 3Differing opinions

Early life[edit]

He was born on August 23, 1936, in Blacksburg, Virginia. Lucas lost an eye at age 10 after it became infected due to a fight.[1] A friend later described him as a child who would often get attention by frighteningly strange behavior.[2] Aside from this, Lucas' mother was a prostitute who would force him to watch her have sex with clients and cross dress in public.[1][3]

In December 1949, Lucas' father, Anderson, whose legs had been severed in a railroad accident, died of hypothermia after going home drunk and collapsing outside during a blizzard. Shortly thereafter, while in the sixth grade, Lucas dropped out of school and ran away from home, drifting around Virginia. Lucas claimed to have committed his first murder in 1951, when he strangled 17-year-old Laura Burnsley, who had refused his sexual advances. As with most of his confessions, he later retracted this claim. On June 10, 1954, Lucas was convicted on over a dozen counts of burglary in and around Richmond, Virginia, and was sentenced to four years in prison. He escaped in 1957, was recaptured three days later, and was subsequently released on September 2, 1959.[4][5]

In late 1959, Lucas traveled to Tecumseh, Michigan to live with his half-sister, Opal. Around that time, Lucas was engaged to marry a pen pal with whom he had corresponded while incarcerated. When his mother visited him for Christmas, she disapproved of her son's fiancée and insisted he move back to Blacksburg. He refused, after which they argued repeatedly during the visit about his upcoming nuptials.

Matricide[edit]

On January 11, 1960, in Tecumseh, Michigan, Lucas killed his mother during an argument regarding whether or not he should return home to her house to care for her as she grew older. He claimed she struck him over the head with a broom, at which point he stabbed her in the neck. Lucas then fled the scene. He subsequently said,

All I remember was slapping her alongside the neck, but after I did that I saw her fall and decided to grab her. But she fell to the floor and when I went back to pick her up, I realized she was dead. Then I noticed that I had my knife in my hand and she had been cut.[This quote needs a citation]

She was not in fact dead, and when Lucas's half-sister Opal (with whom he was staying) returned later, she discovered their mother alive in a pool of blood. She called an ambulance, but it turned out to be too late to save Viola Lucas' life. The official police report stated she died of a heart attack precipitated by the assault. Lucas returned to Virginia, then says he decided to drive back to Michigan, but was arrested in Ohio on the outstanding Michigan warrant.

Lucas claimed to have killed his mother in self-defense, but his claim was rejected, and he was sentenced to between 20 and 40 years' imprisonment in Michigan for second-degree murder. After serving 10 years in prison, he was released in June 1970 due to prison overcrowding.

Drifter[edit]

In 1971, Lucas was convicted of attempting to kidnap three schoolgirls. While serving a five-year sentence, he established a relationship with a family friend and single mother who had written to him. They married on his release in 1975, but he left two years later after his stepdaughter accused him of sexually abusing her. Lucas began moving between various relatives and one got him a job in West Virginia, where he established a relationship that ended when his girlfriend's family confronted him about abuse.

Lucas befriended Ottis Toole, and settled in Jacksonville, Florida, where he lived with Toole's parents and became close to his adolescent niece Frieda 'Becky' Powell, who had a mild intellectual impairment. A period of stability followed, with Lucas working as a roofer, fixing neighbors' cars and scavenging scrap.[7][8][9]

Murders[edit]

Powell was put in a state shelter by the authorities after her mother and grandmother died in 1982. Lucas convinced her to abscond and they lived on the road, eventually traveling to California, where an employer's wife asked them to work for her infirm mother, 82-year-old Kate Rich, of Ringgold, Texas. Rich's family turned Lucas and Powell out, accusing them of failing to do their jobs and writing checks on her account. While hitchhiking they were picked up by the minister of a Stoneburg, Texas religious commune called 'The House of Prayer'. Believing Lucas and the 15-year-old Powell were a married couple, he found Lucas a job as a roofer while allowing the couple to stay in a small apartment on the commune. Powell had become argumentative and homesick for Florida, and Lucas said she left at a truck stop in Bowie, Texas. According to some of his later accounts Lucas murdered Powell and then Rich.[10] In addition to confessing, Lucas led the police to remains said to be Powell and Rich, although forensic evidence alone was inconclusive and the coroner stopped short of positively identifying either set of remains. As with most of his alleged crimes, Lucas later denied involvement, but the consensus is he did murder Powell and Rich.[11]

Arrest, confession to murders of Powell and Rich[edit]

Lucas was a prime suspect in the killing of Rich. A few months later, in June 1983, he was arrested on charges of unlawful possession of a firearm by Texas RangerPhil Ryan. Lucas reported that he was roughly treated by bullying inmates in prison and attempted suicide. Lucas claimed that police stripped him naked, denied him cigarettes and bedding, held him in a cold cell, tortured his genitalia, and did not allow him to contact an attorney. After four days, Lucas confessed to the murder of Rich, which confession investigators had good reason to believe was genuine; in addition, he confessed to killing Powell. When he started confessing to numerous unsolved cases, he was initially credible; police knew that he had truthfully admitted committing two killings. Some investigators, including Ryan, thought many of Lucas's confessions were made up to get out of his cell and improve his living conditions.[12] They did, however, treat dozens as potentially genuine.[13]

False confession spree[edit]

Harry The Serial Killer

In November 1983, Lucas was transferred to a jail in Williamson County, Texas. In interviews with Texas Rangers and other law enforcement personnel, Lucas continued to confess to numerous additional unsolved killings. It was thought that there was positive corroboration with Lucas's confessions in 28 unsolved murders, and so the Lucas Task Force was established.[12] Eventually, because of Lucas's confessions, the task force officially 'cleared' 213 previously unsolved murders. Lucas reportedly received preferential treatment rarely offered to convicts, being frequently taken to restaurants and cafés. Some of his alleged treatment was odd for someone whom the police supposedly believed to be a cunning mass murderer: he was rarely handcuffed, often allowed to wander police stations and jails at will, and even knew codes for security doors.[14][15]

Later attempts at discovering whether Lucas had actually killed anyone apart from Powell and Rich were complicated by Lucas's ability to make an accurate deduction that seemed to substantiate a confession. In one instance, he explained how he had correctly identified a victim in a group photograph through her wearing spectacles; a pair of glasses were on a table in a crime scene photo shown to him earlier. There were also suggestions that the interview tapes showed that, despite Lucas' supposedly low IQ, he had adroitly read the reactions of those interviewing him and altered what he was saying, thereby making his confessions more consistent with facts known to law enforcement. The most serious allegation against investigators, that they had let Lucas read case files on unsolved crimes and thus enabled him to come up with convincingly detailed confessions, made it virtually impossible to determine if, as some continue to suspect, he had been telling the truth to the Lucas Task Force about a relatively large number of the murders.[16]

In 1983, Lucas claimed to have killed an unidentified young woman, later identified as Michelle Busha, along Interstate 90 in Minnesota. When questioned by police, he gave inconsistent details on the way he murdered the victim and was eliminated as a suspect.[17]

In 1984, Lucas confessed to the murder of an unidentified girl who was discovered shot to death in a field at Caledonia, New York on November 10, 1979. The unidentified girl was referred to at the time as 'Caledonia Jane Doe'. Investigators, however, found insufficient evidence to support the confession.[18] In early 2015, over 35 years later, 'Caledonia Jane Doe' was identified through a DNA match as Tammy Alexander.

Lucas also is believed to have falsely confessed to the 1980 slaying of Carol Cole in Louisiana. Cole was unidentified until 2015.[19]

Discredited[edit]

Journalist Hugh Aynesworth and others investigated the veracity of Lucas's claims for articles that appeared in The Dallas Times Herald. They calculated that Lucas would have had to use his 13-year-old Ford station wagon to cover 11,000 miles (17,700 kilometres) in one month to have committed the crimes police attributed to him.[3] After the story appeared in April 1985 and revealed the flawed methods of the Lucas Task Force, law enforcement opinion began to turn against the claims that crimes had been solved.[20][21] The bulk of the Lucas Report was devoted to a detailed timeline of Lucas's claimed murders. The report compared Lucas's claims to reliable, verifiable sources for his whereabouts; the results often contradicted his confessions, and thus cast doubt on most of the crimes in which he was implicated. Attorney General Jim Mattox wrote that 'when Lucas was confessing to hundreds of murders, those with custody of Lucas did nothing to bring an end to this hoax' and 'We have found information that would lead us to believe that some officials 'cleared cases' just to get them off the books'.[15]

Commutation of death sentence[edit]

Lucas remained convicted of 11 homicides. He had been sentenced to death for one, a then-unidentified woman dubbed as 'Orange Socks,' whose body was found in Williamson County, Texas, on Halloween 1979, even though the court heard that on that date a timesheet had recorded his presence at work in Jacksonville, Florida.[22][23][24][25][26][27] Lucas was granted a stay on his death sentence after telling a hearing that the details in his confession came from the case file, which he had been given to read. The sentence was commuted to life in prison in 1998 by Governor George W. Bush.[28] In 2019 'Orange Socks' was officially identified as Debra Jackson.[29]

Death[edit]

Henry Serial Killer Hotel

On March 12, 2001, at 11:00 pm, Lucas was found dead in prison from heart failure at age 64. He is buried at Captain Joe Byrd Cemetery in Huntsville, Texas. As of 2012, Lucas' grave is unmarked due to vandalism and theft.[30]

Differing opinions[edit]

Lucas' credibility was damaged by his lack of precision: he initially admitted to having killed 60 people, a number he raised to over 100 victims, which police accepted, and then to a figure of 3,000 that led to him not being taken seriously. He remained, however, publicised as America's most prolific murderer, despite denials such as flatly stating 'I am not a serial killer' in a letter to author Shellady.[10][31][32] Some continue to believe he was responsible for a huge number of killings nonetheless. Eric W. Hickey cites an unnamed 'investigator' who interviewed Lucas several times and who concluded that Lucas had probably killed about 40 people.[33] Such assertions were given little credence, with lawmen involved with Lucas seen refusing to admit that they had been fooled by him.[34][35]

Unresolved suspicions[edit]

One highly experienced Texas Ranger who Ryan's team allowed access to Lucas said that although it was obvious to him that Lucas often lied, there was an instance where he demonstrated guilty knowledge. 'I remember him trying to cop to one he didn't do, but there was another murder case where I'll ... if he didn't lead us right to the deer stand where the murder took place. Ain't no way he could've guessed that, and I damn sure didn't tell him. I think he did that one.'[35] Other Rangers had similar experiences with Lucas.[36]

Media[edit]

There have been several books on the case. Four narrative films have been made based on Lucas' confessions: 1985's Confessions of a Serial Killer, 1986's Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, played by Michael Rooker, 1996's Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, Part II, and the 2009 film Drifter: Henry Lee Lucas. Two documentary films were released in 1995: The Serial Killers and the television documentary, Henry Lee Lucas: The Confession Killer.

An A&E Biography episode about Lucas aired in 2005 that featured future horror film director Dylan Greenberg as young Lucas in re-enactments, at the age of eight.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

- Sture Bergwall, a Swedish 'serial killer' whose confessions are now believed to be fabricated.

References[edit]

- ^ abKarlin, Adam. 'Henry Lee Lucas: The Confession Killer'. The Lineup. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^Scott, Shirley Lynn. 'What Makes Serial Killers Tick?'. truTV.com. Archived from the original on 2010-07-28. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ^ abTexas Monthly Jun 1985, the Henry Lee Lucas Show

- ^'Henry Lee Lucas by Bonnie Bobit'. Crimemagazine.com. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^'Henry Lee Lucas Dies in Prison — ABC News'. Abcnews.go.com. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^Ramsland, Katherine. 'Henry Lee Lucas, prolific serial killer or prolific liar?'. Crime Library. Archived from the original on 2015-02-10. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ^'The Twisted Life of Serial Killer Ottis Elwood Toole'. Fox News. December 16, 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

Toole met Lucas in 1978,'

- ^Biography channel HENRY LEE LUCAS BIOGRAPHY, http://www.thebiographychannel.co.uk/biographies/henry-lee-lucas.html, accessed 6/8/2014

- ^Henry Lee Lucas ; The Confession Killer (Documentary)

- ^ abShellady, 2002.

- ^see Shellady, 2002

- ^ abThe Times-News - Oct 18, 1983, AP, Texas Ranger Unwilling Confidant Of Henry Lee Lucas

- ^Ivey, Darren L. (2010-04-23). The Texas Rangers: A Registry and History. McFarland. pp. 195–. ISBN9780786448135. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^Gudjonsson, Gisli H. (2003-05-27). The Psychology of Interrogations and Confessions: A Handbook. John Wiley & Sons. p. 556. ISBN9780470857946. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ abquoted in Shellady, 2002

- ^D Magazine, Oct 1985 THE TWO FACES OF HENRY LEE LUCAS

- ^Erickson, David. “Runaway Jane.” Who Killed Jane Doe?, season 1, episode 6, Investigation Discovery, 4 Apr. 2017.

- ^'Case File: 1UFNY'. doenetwork.org. The Doe Network. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^Catalanello, Rebecca (9 February 2015). 'Detectives turn to New Bethany Home for Girls in search of leads in woman's 1981 death'. The Times-Picayune. NOLA. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ^http://www.lrl.state.tx.us/scanned/archive/2009/8145.pdf

- ^Henry Lee Lucas able to confuse authorities and then beat deathArchived February 26, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^Gudjonsson, Gisli H. (2003-05-27). The Psychology of Interrogations and Confessions: A Handbook. John Wiley & Sons. p. 557. ISBN9780470857946. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^Lubbock Avalanche Journal, May 28, 2006 Drifter's confession to Williamson murder failed to hold up

- ^Lunsford, Lance (28 May 2006). 'Drifter's confession to Williamson murder failed to hold up'. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ^'USA: The death penalty in Texas: lethal injustice | Amnesty International'. Web.amnesty.org. 1998-03-01. Archived from the original on November 26, 2007. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^'Today's Headlines — Friday, June 25, 1999'. Ble.org. 1999-06-25. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^Strand, Ginger Gail (2012-04-15). Killer on the Road: Violence and the American Interstate. University of Texas Press. pp. 157–. ISBN9780292726376. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^Knox, Sara L. (2001). The Productive Power of Confessions of Cruelty. Jefferson.village.virginia.edu. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^''It's A Big Deal': Victim In 40-Year-Old 'Orange Socks' Cold Case Identified'.

- ^'Eternity's gate slowly closing at Peckerwood Hill.' Houston Chronicle. August 3, 2012. Retrieved on March 16, 2014.

- ^Brad Shellady, 'Henry: Fabrication of a Serial Killer', included in Everything You Know Is Wrong: The Disinformation Guide to Secrets and Lies, 2002; Russ Kick, editor.

- ^'USA: Fatal flaws: Innocence and the death penalty in the USA | Amnesty International'. Web.amnesty.org. 1998-11-12. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^Hickey, Eric W., Serial Murderers And Their Victims, Wadsworth Pub Co. 2005; ISBN0-495-05887-4

- ^Lawrence Journal-World October 16, 1983

- ^ abTexas Monthly Feb 1994 The Twilight of the Texas Rangers

- ^Interview With MAX WOMACK Texas Ranger, Retired ©2006, Robert Nieman

Portrait Of A Serial Killer

Further reading[edit]

- Brad Shellady, 'Henry: Fabrication of a Serial Killer', included in Everything You Know Is Wrong: The Disinformation Guide to Secrets and Lies, 2002; Russ Kick, editor.

- Henderson, Jim (1998-06-28). 'Henry Lee Lucas able to confuse authorities and then beat death'. Houston Chronicle. Section A, Page 1, 2 STAR Edition.

- Nelson, Melissa (2007). 'Sheriff's wife among 4 dead in shooting'. MSNBC.com. Associated Press.